You might call it either the “Great Teflon War” or “The Battle of Massachusetts,” but either way, the fight took place in the courtrooms of The Bay State, rather than in its cities or countryside. No matter how it’s labeled, however, the victory prize was substantial: rights to the patent for the first functional bidirectional elastomer-seated ball valve.

A BATTLE HARD FOUGHT

The saga began in the laboratories of the DuPont Chemical Company in the years preceding World War II. Chemist Roy Plunkett was searching for a new form of refrigerant when he stumbled upon polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE) resin quite by accident. After creating his “mistake,” however, he began to analyze the sample and discovered that the properties of the new compound were unmatched by any other material. At this point DuPont knew it had a winner, and so it coined and registered the trade name “Teflon” to identify the new substance.

The new material was immediately put to work in a secret endeavor in which DuPont assisted the government—The Manhattan Project. Teflon was used for gaskets and seals to contain the corrosive uranium hexafluorides and other tough applications required for the atomic bomb project.

At about the same time (1942-1943), the Navy was having trouble fighting shipboard fires and needed a better spray nozzle, one that could create a blanketing fog to smother a fire. A young engineer for the Rockwood Sprinkler Company, Howard G. Freeman, solved the problem and created a fog nozzle. The Navy was impressed and called upon Rockwood and Freeman for other solutions. During this period, Rockwood also became involved with the Manhattan Project. As an insider, Freeman learned all about the new DuPont Teflon material and the miracles it could accomplish.

TEFLON AND VALVES

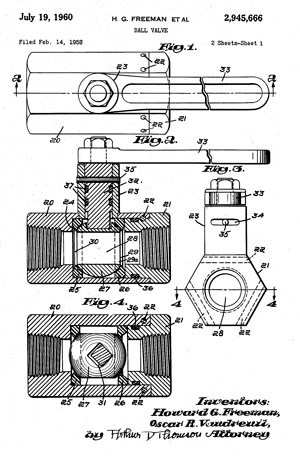

Howard Freeman, although well compensated at Rockwood, yearned to start his own company and create the first bidirectional, zero-leakage ball valve. Freeman left Rockwood Jan. 25, 1955. His new company, called Jamesbury, began business the next month as Freeman put his ideas for bidirectional seats on paper and began making the valves. The key to the valve’s success and the heart of the patent was the design of the flexible Teflon seats, which created a positive seal in either direction. Freeman filed for a patent on the design in February of 1958 and patent #2945666 (a.k.a. the “666” patent) was granted in July of 1960.

NEXT UP: BATTLING WITH GOVERNMENT

The U.S. Navy was an early proponent of the Jamesbury valve for use in its submarines. It was quiet, easy to open and close, and leak tight. Unfortunately, shortly after Jamesbury’s initial sales to the government for the U.S. nuclear navy, the Navy allowed other suppliers, including prime contractor, Electric Boat, to infringe on its patent. Electric Boat began building Jamesbury-designed valves without permission thinking that “little” Jamesbury wouldn’t fight the Navy’s favorite son, Electric Boat. They were wrong.

Jamesbury filed suit against the government as well as all the vendors that manufactured Jamesbury-patented designs. It wasn’t until 1980 that the suit against the government was successfully won by Jamesbury, and other suits against vendors in this case were not settled until as late as 1988.

An interesting anecdote to the Teflon ball valve story surrounds the patent by Crane Valve Company for a soft-seated ball valve design (also called a spherical plug valve), patent number 2373628, which was granted in 1945. The Crane design used spring-loaded, graphite-impregnated rubber seats for bidirectional sealing. It is not known how well the valve actually worked because during those booming post-war years, Crane decided to concentrate on other valve types. According to a retired Crane engineering manager, at that time “the company could see no useful purpose in that type of valve design and that future sales success could not be guaranteed.” Obviously, timing is everything, including in the valve business. Perhaps if Crane, while it was assisting with the Manhattan Project and nuclear navy projects, had learned of and applied the technology of Teflon to their ball valve seats, history would be different.

BIDIRECTIONALS GROW IN USE

And of course, the entire nation now knows about the wonders of Teflon, though most of us think about non-stick cookware. No doubt chemist Roy Plunkett would be both surprised and pleased at what his invention has wrought.

GREG JOHNSON is president of United Valve (www.unitedvalve.com), Houston, and is a contributing editor to VALVE Magazine. He serves as chairman of VMA’s Education & Training Committee, is a member of the VMA Communications Committee and is president of the Manufacturers Standardization Society. Reach him at greg1950@unitedvalve.com.

RELATED CONTENT

-

A History Made in Metal

Today’s valve material choices are like a Chinese buffet: Everything imaginable is on the menu.

-

A Reference Manual on Elastomers

The history and general application of elastomers in pipes, valves and fittings is the subject of the Manual of Practice developed by the American Water Works Association (AWWA).

-

The Intriguing Story of the Pressure Seal Valve

In a quest for more efficient power generation, power plants in the 1930s pushed the pressure-temperature envelope.

Unloading large gate valve.jpg;maxWidth=214)