Pneumatic Valve Actuators in Sub-Arctic Climates

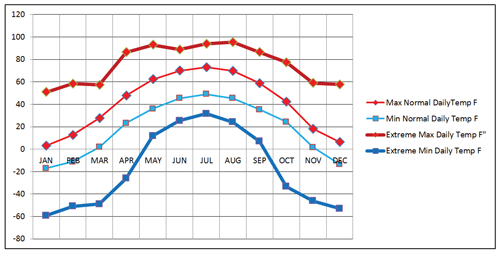

Sub-arctic climates experience temperatures from 100° F (38° C) in the summer to –60° F (–51° C) in the winter (Figure 1). While there is nothing spectacular about the high end of the range, the low end impacts the functionality of pneumatic actuators.

#actuators

WHAT CAN HAPPEN

There is never a good time for an actuator to fail, but a failure when the temperature is at 60 below or when a blizzard limits capacity for transporting repair parts could be especially troublesome. Careful selection of valve actuation is critical.

- The actuator housing is steel.

- The drive shaft is a precipitation-hardened stainless steel.

- The seals are buna.

- The shaft bushings are Nylon 6.

With these parameters in mind, at –60° F (–51° C):

The steel housing has become brittle. It is not necessarily weaker, but a sudden impact or an imperfection that would have no effect on the metal when ductile, could result in a sudden fracture at these sub-zero temperatures because the temperature is below the brittle transition temperature of steel. The question “will it fail at –60° F?” cannot be answered without knowing if there will be sudden impact loading, but possibility of failure has increased there.

The precipitation-hardened shaft material has also become brittle and may fracture given an impact load. If, for example, the driven valve resists opening and then breaks free, the resulting sudden impact may cause the actuator shaft to fail.

The shaft material will have contracted at a rate of 9.4 by 10–6 per inch of diameter per degree F, while the Nylon 6 bushings will contract at a rate of 44.2 x 10–6 per inch per degree F. If the original gap between the bushing bore and the shaft surface was .002 inches and if the shaft diameter was 3 inches, then 130° F (54° C) temperature change from 70° F (21° C) to –60° F (–51° C) would contract the shaft diameter to 2.996 inches and the 3.002 inches diameter bushing bore to 2.985 inches, causing binding and failure.

The buna seals have turned to stone. Their normal resiliency, which allows flowing into and sealing leak paths, is gone. The seals cannot flex and leakage will occur at all seal points resulting again in actuator failure.

THE SOLUTION

Failure of the example standard actuator is a certainty in this case. While there is nothing in the above example that is not obvious to every designer and user, the solution to avoid failure is to apply what we know.

Metals

For example, metals that have a brittle transition temperature that falls within the range of possible application temperatures should not be used unless absolutely no impact loads can occur. Examples of suitable metals are 300 series stainless steel and aluminum—neither has brittle transition temperature. Because of its greater strength, stainless steel may be the best choice for larger actuators.

Figures 3 and 4 show a simplistic representative impact test performed on a notched steel bar. One end was locked in a vice, and a hammer blow served to provide an impact. At room temperature, the hammer blow bent the specimen, but there was no fracture.

Figures 5 and 6 show an identical specimen that was brought to a temperature of –60° F. (An interesting side note is that the air cans used to clean a keyboard, when turned over, emit a liquid that has a measured temperature of –60° F, which proved convenient for testing.)

If at all possible, where there is close fit between moving parts, select materials having the same coefficients of thermal expansion/contraction (Figure 7).

Seals

Designers and users who read this may respond: “We’ve used essentially standard actuators and all we did was select a seal material that remained resilient at the low temperatures.” This article is not stating such a combination will fail, only that it may fail—the steel plates of the Titanic may not have fractured if it had not hit the iceberg, and not all World War II Liberty ships cracked in half. But by considering the above suggestions, the supplier can greatly reduce the risk of failure.

USERS

Users, as well as designers, have responsibilities regarding pneumatic actuators under extreme cold conditions.

First, and most obvious, users should shelter the actuator from weather extremes where possible. Second, users must assure a dry air supply, at least 15° F (–9° C) below the lowest temperature that may be experienced since ice plays havoc with air flow and mechanical motion. Finally, users should assess the recommended actuator and whether all possible precautions have been incorporated by the supplier.

Clearly, pneumatic actuators can perform their intended functions despite having to operate in extreme temperatures. However, they need to be designed and manufactured properly, and users need to take responsibility to keep them functioning correctly.

Ed Holtgraver is designer, founder and CEO of QTRCO, Inc. (www.qtrco.com), Tomball, TX. He holds numerous valve and actuator patents with more in the application stage. Holtgraver is a member of the VMA Board of Directors, Education and Training Committee, and Valve Magazine’s editorial review board. Reach him at ed@qtrco.com.

RELATED CONTENT

-

How the EPA's Emissions Rule May Impact Actuator Choices

The move toward net zero emissions by 2050 was just released as part of the COP28 meeting in Dubai.

-

Linear Actuators for Automating Gate Valves

Most professionals in the valve industry are already familiar with the use of linear actuators to operate globe valves.

-

Grease for Motor Actuator Maintenance

Maintaining the right amount of grease inside motor actuators that use grease for lubrication is a vital part of valve maintenance, and can save time and money by preventing problems before they happen.

Unloading large gate valve.jpg;maxWidth=214)