ESG: Environmental, social and governance. Sustainability. Renewables. Decarbonization. Net zero. In the lexicon of the world’s pressing energy transition, these terms dominate the new narrative. The reasons for this shift are varied, complex and numerous, but chief among them is changing corporate priorities that more deliberately consider not just shareholders but also a broader and critical group of stakeholders like communities, employees and customers. Capitalism is going through a transformation that acknowledges climate risk, and the International Energy Agency (IEA) has laid out its plans for net zero emissions by 2050 with a majority of vital OECD (Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development) countries in support.

For people who have spent their careers in industry, energy and manufacturing dating back some 30+ years, ESG is a major change that poses multi-faceted hurdles and likely a fair amount of resistance. It’s an approach that challenges outmoded notions of increasing profits at all costs in a time of unfettered capitalism. It weighs industry’s impact on the world, especially when considering the environment and issues of sustainability.

Discussing these ESG themes at the in-person VMA Valve Forum in April, Mike Troupos, managing director, Foresight Management, expanded on the investment aspect during his presentation Green Drives Green: How Embracing Sustainability Lowers Operating Costs, Increases Sales and Creates a More Resilient Company, “If you haven’t heard of Blackrock, the company is the globe’s largest asset manager where trillions of dollars of stocks are owned.” He added, “Blackrock CEO Larry Fink has pushed hard in the past couple years, saying plainly that climate risk is investment risk.” Troupos quoted Fink as having argued, “The evidence on climate risk is compelling investors to reassess core assumptions about modern finance. In the near future — and sooner than most anticipate — there will be a significant reallocation of capital.”

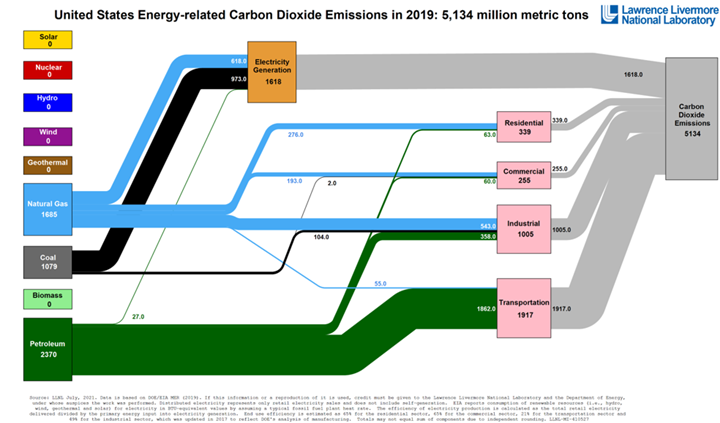

The U.S. energy landscape. Photo credit: Mitsubishi Heavy Industries and Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory

Looking at the social part of ESG — and partially impacted by COVID’s effect on the workplace and job satisfaction — there’s a shift to more employee-centric approaches in valuing what each and every person brings to the table and the importance of bringing jobs back to the United States as we push to stay innovative and regain a strong foothold in manufacturing after decades of outsourcing jobs overseas.

In addressing the last part of the ESG triad — governance — Troupos also talked about a new Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) mandate that was recently approved in March 2022 titled The Enhancement and Standardization of Climate-Related Disclosures for Investors. This rule, once it’s in place, will mandate companies to report greenhouse gas emissions on their annual reports, ranging from Scope 1 to Scope 3, which is a progression from direct to more indirect, respectively. And he pointed out that all those in attendance at the conference — whether working for publicly traded companies, private equity (PE) firms or family-owned businesses — fall into the category where their scope 3 (indirect) emissions are drastically larger than their Scope 1 or 2 emissions.

HYDROGEN ON THE RISE

Pertinent to the valve industry in particular, Troupos discussed the major role valves along the entire value chain will have in the future of our economy, especially in green infrastructure like hydrogen technologies. With it expected to play a significant part in a net-zero path, hydrogen service relies heavily on valves in dealing with high pressure and cryogenic temperatures.

Pradeep Venkataraman, senior manager at Mitsubishi Heavy Industries America, who presented on the Role of Hydrogen in Energy Transition at the Valve Forum, explained the challenges with hydrogen: “We have an efficiency problem. It’s the lightest gas and it takes a lot to compress hydrogen to the density needed and transport it…it’s much more energy-intensive than natural gas. We’ve flown astronauts on spacecraft powered by liquid hydrogen, so there’s a lot of knowledge about how to handle and produce hydrogen, but the challenge is how to do it at scale and in an economically feasible way.”

If we can tackle the hydrogen problems of energy density, safety and the bottleneck in transportation and storage (where valves play a major part), Venkataraman said, making the element safe for consumer use on a mass scale is a significant step toward a lower-carbon future. There are currently more than 150 fuel cell electric vehicle [FCEV] fueling stations throughout the country (primarily in California), with 4,300 expected by 2030.

A repeating theme is that this gargantuan effort and energy transition will have myriad paths, so it’s crucial to employ all opportunities and technologies to come anywhere close to net zero emissions by 2050. In clarifying this point, Venkataraman explained, “It’s a combination of a lot of different solutions. We have to look at carbon capture and storage (see sidebar), automate sources like electrification, hydrogen and renewables replacing fossil fuels; it has to be all and not just one.”

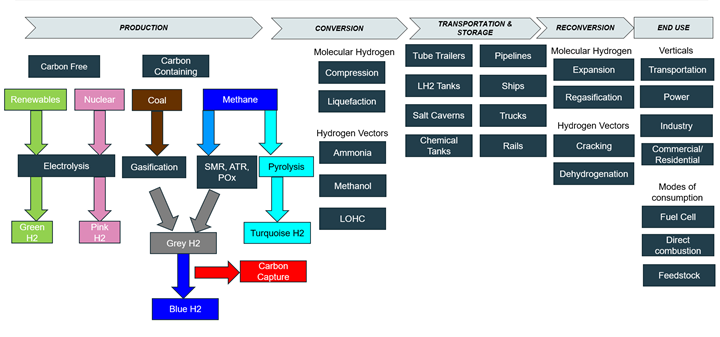

Hydrogen’s hues. In terms of producing hydrogen that is useful, there are three methods: natural gas reforming, coal gasification and electrolysis. Based on the amount of GHG emissions generated, they are broken down into five color descriptors (Figure 2):

- Green — No GHGs are generated, as renewable sources such as wind or solar provide the energy to split the hydrogen and oxygen.

- Blue — The carbon generated in thermal processes is captured and stored underground (CCS).

- Gray — Natural gas is used as a primary source (the most common form of hydrogen generation) and produces fewer GHGs than brown hydrogen.

- Brown — It uses black (bituminous) or brown (lignite) coal as a primary source of hydrogen; it generates the most GHGs.

- Pink — This hydrogen is generated through electrolysis powered by nuclear energy. It is also sometimes referred to as purple or red hydrogen.

Broadly speaking, the IEA predicts that hydrogen demand is projected to grow fivefold by 2050, primarily by road transport, maritime and aviation — and remarkably, its supply is expected to shift from almost 100% gray hydrogen to 95% clean green production by mid-century as costs decline and policymakers favor hydrogen technology adoption.

FOSSIL FUELS STILL REIGN SUPREME

The reality is that the world is still on a path of fossil fuel demand peaking between 2023 and 2025, according to McKinsey & Company’s Global Energy Perspective 2022. Presenter Gabriel Collins, Baker Botts Fellow for Energy and Environmental Regulatory Affairs at the Baker Institute for Public Policy, Rice University, discussed this theme in his session: “If we look at empirical evidence from the last 50 years, one of the things we see is that energy insecurity can really undermine climate goals. We didn’t think about this as a climate goal in the 1970s when we had the oil shock and Wyoming became a coal super giant in global terms. But if we’re looking through today’s lens, it’s something I think would undermine these goals. What you see over and over is during a time of crisis, whatever’s installed, reliable and cheapest is going to tend to win out.”

Of course, a major complicating factor that adds uncertainty to a net-zero economy and infrastructure is the war in Ukraine. Russia’s role as one of the world’s largest producers of oil, gas and commodities is already causing ripple effects in Europe where countries like Germany and the United Kingdom rely heavily on supply from Russia that has been curtailed in retaliation to sweeping sanctions.

These macro events, like COVID, Russia invading Ukraine, U.S.-China diplomatic tensions, domestic and international politics, supply chain issues and inflation, greatly impact the overall complexion of the world’s energy needs and efforts of the IEA and the Paris Agreement. The volatility isn’t going to go away moving forward.

Collins continued, “We will see a lot of efforts to talk about ESG, but the flip side of this, especially with some of the bigger industry players divest assets, whether it’s oil sands or a coal mine, these things are rarely shut down.” Reflecting the nebulous nature of this transition we’re in the midst of, however, Collins also theorized, “If we continue to have high commodity prices, if anything, the pressure on this front probably intensifies for certain investment pools to loosen up on constraints and actually take advantage of market opportunities that are being presented to them.”

Wrapping up his presentation to finish on a generally positive note that takes the long view, Collins said, “A tough decade lies before us, but we can do this. The very fact that humanity has industrialized so successfully and that we are forced now to confront emissions issues on this scale is in itself a cause for celebration given where we were as a species just 500 years ago. At the same time, billions of our kin still suffer from energy poverty. It’s a global Manhattan Project-scale endeavor, but I’m hopeful we’ll get it done despite the bumps in the road.”

RELATED CONTENT

-

Five Reasons Why the Right Strategy Leads to the Success of Digital Transformation Implementation

The past few years have proven that digital transformation (DT) is more than just a trend. It is becoming one of the frontrunners for ensuring business continuity through modernizing times. However, despite being an essential component for adaptability in a competitive industry, not all companies would consider their DT implementation a success.

-

Piping Codes and Valve Standards

As with every intended use for valves, piping carries its own set of standards that valve companies and users need to understand.

-

Process Instrumentation in Oil and Gas

Process instrumentation is an integral part of any process industry because it allows real time measurement and control of process variables such as levels, flow, pressure, temperature, pH and humidity.

Unloading large gate valve.jpg;maxWidth=214)