Understanding Generational Differences

A universal issue that comes up at almost any event today is the need to attract new people with the right skills into the specialized, technical fields where valves and control devices are made and used.

#basics #VMAnews

Marilyn Moats Kennedy, a workforce issues specialist and speaker at VMA events, uses this story to illustrate the problem:

“One of the worst things I ever saw happened at an insurance company new employee orientation. This guy got up before a group of young people and announced: ’17 years ago, I sat where you are sitting now,’” Kennedy explains. That might have flown many years ago when the speaker was a young man, she says, but: “What he didn’t know was that his audience members were saying to themselves: ‘Oh my. Couldn’t he get a decent job?’”

The problem was that the speaker came from the baby boomer generation, but his audience was part of the millennial and younger generations, which have an entirely different set of values.

“He had no understanding that you don’t talk longevity to people who live in the moment,” Kennedy says. “If the worst thing you’ve experienced to date is a bad hangover from a long night or if you’re still living in your parents’ house, longevity in a job is not your goal,” she says.

THE GENERATIONS

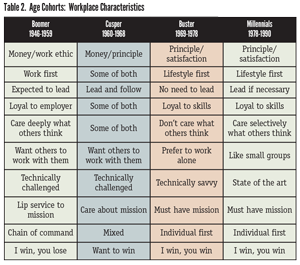

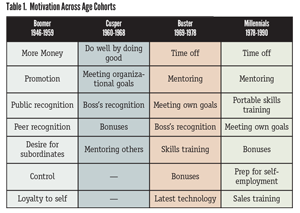

For purposes of illustrating her point and explaining how different generations came to be, Kennedy uses these four groups as reference points for most of the workforce:

- Baby Boomers born in 1946 to 1959 (ages 55-68—about 38% of the population)

- Cuspers born 1960-1968 (ages 46-54—11%)

- Busters born 1969 (ages 36-45—20%)

- Millennials born 1978-1990 (ages 24-36—15%)

One of the major differences between the oldest and youngest of these groups is that when baby boomers were entering the workforce, they were driven by the need to make money or, like with the speaker at the insurance company, have a career. Millennials are driven by principles and the need for self-satisfaction.

“Boomers are focused on upward mobility and buying more things because that is the model of post-World War II America,” Kennedy explains. Younger generations “just want to be able to cover their costs. They do not want more things. One of their major goals is to see that their children graduate college debt-free and that they save for retirement,” she says.

When it comes to the workplace, the two are very different in how they view getting things done. Boomers, for example, have been taught to take a team approach.

This is because their upbringing was influenced by parents who went through World War II—parents who looked to the U.S. military as an example of how to get things done.

“What we forget, however, is the amount of training military forces have for making teamwork operate—much more than anyone in private industry could afford,” Kennedy comments.

Even baby boomers today have learned there are flaws in the idea that everything is best done through teamwork.

They’ve learned over time that “each of the members of a team will not do the same amount of work,” she says, and they have learned to put systems into place for accountability.

Meanwhile, when today’s young people were children, teachers and coaches presented them with the idea that “everyone gets the same ribbon” for participating in a sport or academic challenge, Kennedy explains. Such thinking “diminishes what you do as an individual.” As a result, they now have the attitude that “I’m going to be responsible for my own work. I want to do the job on my own and be evaluated on my own,” she explains.

Another great difference is how important personal values and the freedom to express those values are in the workplace.

Older workers tend to participate in community service for its social and professional benefits so they join organizations such as the local Rotary or professional organizations, she says. Younger workers believe it’s important for the company itself to be cause-oriented.

When they are deciding where they want to work, “They want to know what the owner truly values. Does he or she support the Salvation Army, participate in Big Brothers and Sisters, or stand up for environmental causes? The younger generation may not pick a job based on those causes, but they want to know the boss occasionally thinks about something other than the bottom line,” Kennedy says.

HOW IT TRANSLATES

To get the needed fresh blood for industry will require the older people to understand what appeals to today’s youth, Kennedy explains.

She suggests the industry start by appealing at the junior high level. “Early and repeated exposure to your industry is important, and I’m amazed that more valve and industrial company professionals don’t go into the schools, bring a pizza, sit down and tell these young people the advantages of what they do,” she says.

They need to start early because young people need to see how a professional can get from Point A to Point B with a career in industry or manufacturing.

“Think about how many people go into medical school because they have high scores on the MCATS [Medical College Admission Test]. It’s not that they want to treat people initially—they just get on a track that begins with doing well on a test,” she points out.

The valve industry also should be reaching out to the nation’s technical schools to find candidates who may have a real interest in technical fields.

She suggests that for technical school students, companies sponsor regular “day on the job” tours of plants.

“Here’s a big conflict that comes with talking to today’s youth,” she explains. “When you’re dealing with someone who is 18 or younger, you have to realize that the one thing he or she is not eager to do is to get a white collar job and die at a desk.”

Kennedy also says that too often, she sees industry technical professionals who are talking to young people who almost apologize because the work is hard or repetitive.

“They are putting ideas in young people’s minds that are negative when they should be talking about outcomes—not about making widgets. It would be so much better to start with a tour of a facility and show them exactly what the job looks like and what the product does,” she says.

To appeal to the millennial generation, for example, they need to show how those widgets meet specific needs because that generation loves to solve problems.

Not many people know how vital valves are in the infrastructure of the nation—how they are in everything from pipelines to building operations.

“Your websites and your presentations should be telling people what valves are, who uses valves and what that means to the world,” she says. “Don’t assume they know, because they don’t.”

What is not needed in dealing with today’s younger generations is to tell them: “‘Someday you’ll be owner of a company.’ That is not what they want to hear. They want to know what they might be doing in three weeks, then three months, then three years,” she says.

They also want assurance that what they will be doing will be useful and effective.

Kennedy pointed to the paint industry as a place where certain companies have been effective in doing just that by linking painting to sustainability.

“Some of the companies have been able to show how vital painting can be to the environment and how working for the right paint company can make a difference because of it,” she says.

Industries trying to appeal to the young today have to relate what they do to the good of the nation, to the economy, to the environment, she explains.

The boomers are a good source for teaching these lessons because they have seen the industry as it’s evolved, and they’ve personally been on the tracks of movement that can occur within manufacturing companies, she adds.

“Young people want a story from someone believable, so don’t send young people out to recruit other young people. The younger generations want people to tell them personal tales of what the industry did for them. Send those garrulous boomers proud of what they’ve done. Every alumnae group in the country has learned to use this technique and you should, too,” she says.

THE MIDDLE GENERATIONS

For example, while the upper ranks of boomers and even some cuspers are “technically challenged,” the younger generations have not only embraced technology, but made it a daily requirement.

“Companies have to learn to invest in the best today because if you want to appeal to the world’s youth, you can’t even have a whiff of obsolescence. It spooks people,” Kennedy says.

Boomers also need to realize that to appeal to generations not motivated by money requires facing the fact that “forever after no longer exists. If someone is doing a wonderful job after a couple of years, you need to start asking what else he or she would like to learn,” she says.

Those generations moving up the ranks want to know what else they can accomplish in the job. For some, that may mean that the international travel increasingly necessary in the business world may appeal.

It’s also vital to face the reality that the issue of “having it all” that feminism first struggled with is still around, however, and that it’s expanded to include both genders.

“With younger generations focused heavily on lifestyle as vital to their lives as career mobility, both men and women are looking for ways to make their personal lives work,” she says.

The balance issue is a major one at all levels of employment today and companies that can find a way to provide flexibility will retain their workforce best she says.

“The assumption used to be that if you recruited the best and the brightest, they would stay forever. Today, I often tell companies that the competition for good employees is not so much between different companies that steal each other’s talent. The competition is self-employment,” she says.

“There is such a backlash against working in offices today that everyone under the age of 40 wants to work at home,” she adds.

While that can’t possibly happen, “maybe we can look at what that really means. We can concentrate on things they don’t like about the office such as office politics and constant meetings and find ways to give them what they want, such as the chance to participate in social causes and flexibility with family situations,” she says.

She also points out that the youngest generation (those born after 1990) are a different breed, but says that may offer an advantage in the technical fields. Young people have an extreme interest in science and in mechanical things.

“They care about using their hands and making things,” she adds.

Meanwhile, “save your biggest paychecks for the baby boomers” because they’ll need it both for retirement and because that generation was not taught to be frugal. Many were encouraged to use their homes as ATMs, have revamped retirement plans and plan to work until 75 or so. Many did not or could not save what they’ll need to be comfortable in old age or lost significant amounts during the latest recession.

Overall, Kennedy concludes, the companies that give people the means to make their lifestyles work, convince them the company stands for something beyond making money and show them the job and what the company makes is useful to the world, “stand a much better chance of finding and keeping the talent they need.”

Genilee Parente is managing editor of VALVE Magazine. Reach her at gparente@vma.org.

RELATED CONTENT

-

Air Valves in Piping Systems

Liquid piping systems are prone to collecting air from incoming fluids, pumps and connections.

-

The Basics of Eccentric Plug Valves

Wastewater systems present many challenges to pumps and valves because the flow can contain grit, solids and debris, depending where in the process the equipment is located.

-

Fundamental Operation of Pilot-Operated Safety Relief Valves

In this second of a series, we explore another type of pressure relief valves used in common applications.

Unloading large gate valve.jpg;maxWidth=214)