Recycling Foreign Metals: Buyer Beware

The North American steel-making industry, with its historic record of quality control, is no longer the world’s top producer.

#materials #components

Today a large industrial valve can have its body made in a foundry in Belgium, be machined in Germany, be spray coated in France, be shipped to Canada or the U.S. where both assemble the final components that were made in the U.S., and then finally shipped worldwide. Chain of custody papers can be very challenging to read!

Figure 1. Oil field valves, new and used, undergo servicing and inspection in the maintenance shop. A half dozen valves came in one shipment worth $50,000 each—they were unusable. The pressure ratings could not be verified on the paperwork for engineering and insurance code reasons.

Figure 1 shows a group of valves that came to the oil camp where I once worked. The actuators on the left were counterfeit as the nameplates did not match the invoices and those did not match the shipping chain of custody forms. In addition, internal parts were not correct. For the Canadian oil patch, the wait time for delivery on these types of valves exceeded six months. These were ordered from the U.S., but the travel history papers indicated Europe. If there is a problem with these products, who is responsible?

Today’s valve suppliers have much to consider in terms of metallurgy of the components of their valves. The primary concern is the effect of world-wide recycling of metal on component metallurgy.

THE PROBLEM WITH RECYCLED ALUMINUM

Consider the world of recycled aluminum. Billions of aluminum cans are recycled every year with much of the tonnage recovered going to two places: engine blocks and landfills. Aluminum recycling efficiency is potentially a myth.

Recycled aluminum cans have a limited use. They cannot even be used to make new cans because of the impurities at the molecular level that affect the metal’s strength, ductility, tensile strength and toughness values.

When aluminum is continually recycled it loses its quality due to contaminants in the foundry melt furnaces such as oils, paints and other metals. The greatest enemy of recycled aluminum is iron from steel: A product made with new aluminum will be of higher quality than the recycled product. New aluminum cans need perfect metallurgy to handle the stresses made by stamping while engine blocks are more forgiving. In this case, size matters.

Steel coils can have varying physical properties such as strength and ductility even if certified as the same grade.

Although a lot of energy is saved in the recycling process since it avoids the need to make new aluminum from raw ore, it turns out that the recycling process, when repeated, creates serious impurities in the end product.

Researchers at MIT have found that unless specific and extremely expensive processes are introduced into the aluminum recycling market, those impurities will continue to add up—which is why landfills are filling up with crushed cans. Middle East countries, for example, are adding new virgin aluminum ore smelters to fulfill their own needs. They do not want the headaches of dealing with recycled aluminum.

THE CHALLENGES FACING SCRAP DEALERS

The iron foundry where I worked as a metallurgist bought recycled iron and steel. In the semi-truck unloading bay, a large magnet would pick up a ton at a time of scrap, and then shake it to try and drop out the intertwined scrap chrome, stainless steel and aluminum pieces—not always successfully. The scrap loads would come from metal recyclers that tried to sort out the different metal types but the only way to do so would be to hand sort the scrap.

For a few tons, this might be practical though it would still take a day or so. But for a thousand tons a day being shipped all over the country and beyond, it is an impossible task. Scrap dealers do their best but at one Canadian foundry, about 5 to 10% of the recycled scrap coming in was not iron or steel by itself, and a good percentage of this went into the melt furnaces. Although it was hoped most of the contaminants would come to the surface as slag, some always got through into the various cast iron products. Cast iron really does not like aluminum or stainless-steel contaminates.

At a pipe rolling steel mill in Toronto, Ontario, it was one-third the cost to buy the steel from Brazil, ship it by boat to Montreal, Quebec, on the Saint Lawrence River, process it by slitting to size, and put it on trucks and drive to Toronto, then it was to buy from a steel foundry in Hamilton, Ontario, 1 hour away.

The author inspecting one of three 13-ton Brown Boveri Induction furnaces. Before a melt pour that occurred every 20 minutes, molten slag was skimmed off the surface of the furnace.

The metallurgy was not nearly as good, but at one-third the price, it was worth discarding the defective loads of the shipments, before or after further processing. Buying lower quality parts and fabrications can make economic sense but cause big headaches for those on the manufacturing front lines.

A supervisor in charge of a quality control department for an automotive company in Ontario, Canada, reported that parts received for just-in-time delivery came from many countries but mostly from Mexico. Every single part was checked for meeting specs by contract inspectors when they come off the supply trains or trucks. Rejection rates were as high as 95% or more per item. Translate this to hundreds of thousands of parts a week. Yet, it was still cheaper than producing the parts at nearby sub-contracting factory suppliers that had closed across southern Ontario due to foreign competition.

Scrap steel is an internationally traded commodity. Foundries really have no idea where their scrap material originates. It can come from scrapped automobiles, shipyards and even decommissioned nuclear power plants. Determining the metallurgy of this scrap can be brutal—and nearly impossible to do once made into valves.

In 2018 a record-breaking end-of-life shipping tonnage was scrapped on South Asian beaches; 744 large ocean-going commercial vessels were sold to the scrap yards in 2018. Of these vessels, 518 were broken down on tidal mudflats in India and Pakistan. This scrap then was sold around the globe to steel foundries. A ship averages out at 100,000 tons. World steel production in 2018 was about 1,800 million tons and the steel recycled from these ships was about 74 million tons. Almost 4.5% of world steel production came from this scrap steel.

Four-and-a-half percent of scrap steel being melted with 1,800 million tons of total steel may not seem like a big deal—but in terms of steel grades and their allowable alloying percentages, it can be a nightmare in terms of quality control and the respective metallurgical chain of custody forms (COCs).

THE DECLINING QUALITY OF STEEL

The U.S. is no longer the world leader in steel production. This is a terrible situation for fabricators worldwide. Quality of steel is important in terms of individual steel grades and their respective physical properties such as tensile strength and ductility, as well as their chemical properties in terms of corrosion and electrical conductivity.

All steels have minimum and maximum percentage limits to their composition to ensure their physical and chemical properties are maintained. Melting scrap steel with virgin steel is now changing these properties.

Other countries do not have the same quality control that North American steel producers once had. It is all about the raw tonnage produced and the cost to do so. The adage “You Get What You Pay For” has never been more important than in today’s fabricating world.

Fabrication problems with a particular component of a valve may not exist with another piece that comes from another country of origin. Everything comes down to cost to fabricate each component. The metallurgical properties of two components side by side, but coming from two different countries, can make one totally off spec and the other good. Proving this, however, may be outside the capability of a valve supplier.

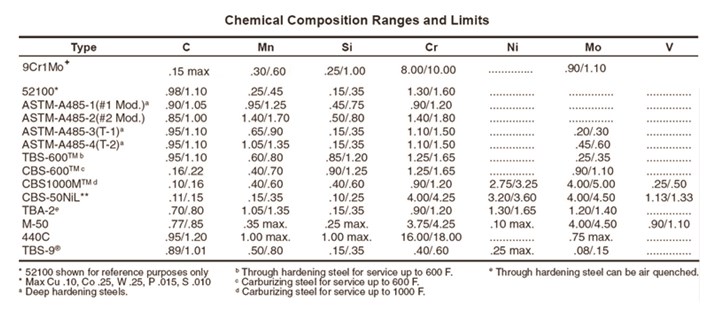

All steel grades have many specific chemical elements such as iron and carbon and each has upper and lower control limits in terms of percentages allowed. Stainless-steel grades have extra amounts of nickel and chromium to give the stainless the required

properties.

If the steel is virgin steel—meaning it contains no recycled steel—then the elemental percentages can be controlled and kept within the specs of each grade, as well as the minor elements.

But with the continuous recycling occurring as steel is made and then eventually recycled as scrap steel, such as with old car bodies, the minor elements are gaining in terms of percentages, often exceeding their maximum allowable amounts. These increases in allowable percentages of what were once considered the minor elements of a grade are now a cause of great concern to the regulating organizations that certify metal grades and the engineering societies that determine codes.

Two of these tablets of pure bismuth, each smaller than a penny, when added to 13 tons of molten white iron, would affect the iron’s ability to be transformed to malleable cast iron when put in a 36-hour annealing furnace.

These elements at the parts per billion level can be very worrisome, depending on the item’s service use. One fabrication or component of steel or iron from Brazil may have different properties from one made in China. Every country/company has different criteria for QA/QC that they follow.

TRACKING THE PARTS

Country of origin matters, not only for composition of metal but also for the quality of the manufacturing process. There will be variations in:

- Quality control

- Heat treatment

- Physical properties

- Chemical properties

- Metal composition at the molecular level

These properties work in unison to give the needed requirements of a particular grade and code when the metal is machined, welded, extruded, pounded, milled, bent and exposed to other physical and chemical attacks. Even subsequent heat-treating processes will be affected.

Valve fabricators and others, for liability protection, need to ensure they have a system to track the parts used from source to the final customer. If multibillion-dollar oil companies are having issues with valves, imagine the difficulty faced by a municipal water treatment plant, for example, that is trying to prevent quality issues.

RELATED CONTENT

-

Ni-Cr-Mo Alloys

Q: How do I know what the best type of Ni-Cr-Mo alloy will be for a particular application?

-

The Materials That Make Up Valves

EDITOR’S NOTE: Materials used in the manufacture of valves and how they perform in different applications is a topic of huge interest to everyone who works with valves.

-

NACE MR0103 Material Compliance

Q: I have a material certified to be compliant with NACE MR0175.

Unloading large gate valve.jpg;maxWidth=214)