The Economics of Valve Repair

The old saying in the valve service industry is “price, quality and delivery—you can pick any two.” That saying is still true 175 years after the first steam valves quit working and needed repair.

#maintenance-repair

THE PRESENT REPAIR WORLD

Although single valves or small batches of valves are repaired for major process and power plants all the time, the greatest influx in the business today comes from dedicated periods of plant maintenance. These intervals are called outages, shutdowns or turnarounds.

During a turnaround, the valve repair company only has so many days and hours to repair valves and bring them back to working condition in accordance with the original design specification or repair standard. This situation could be compared to TV cooking shows where the contestants only have so many minutes to effectively create a well-prepared, succulent dish.

To further that analogy, the TV chefs, at the beginning of the show, often don’t know the ingredients they’ll have. Similarly, a repair company often doesn’t know what valves must be repaired or what condition they’re in until repair personnel come through the door, and the equipment has been inspected. All these repair unknowns mean that accurate pricing is important, both for the service company to cover its costs and make a profit, and for the owner/end user to justify the cost of the repair.

To use a second analogy, a repair procedure is a lot like a visit to the doctor. The ailing person might be feeling a bit fatigued or have some recurring pain. Sometimes the problem will be obvious, and a prescription or treatment will be ordered right away. Sometimes, however, additional investigation is needed so tests are administered to determine what to fix and how. This is similar to the process involved in valve repair.

TOTAL COST OF OWNERSHIP

TCO is probably the most important consideration in the repair/no-repair decision-making process. However essential variables in the TCO equation have changed significantly in the last 20−25 years. Today, many of the valves that would have been fixed two decades ago are not repaired; instead, they are just replaced. This is because the cost of a new valve from a low-cost manufacturing location such as India or China is lower than the cost of basic refurbishing.

Furthermore, before Y2K, valve service companies were regularly repairing 2–6-inch, Class 150 and 300 gate valves. In fact, some facilities had assembly-line refurbishment operations for small cast steel valves that reduced the cost of repair for these valves because of economy of scale.

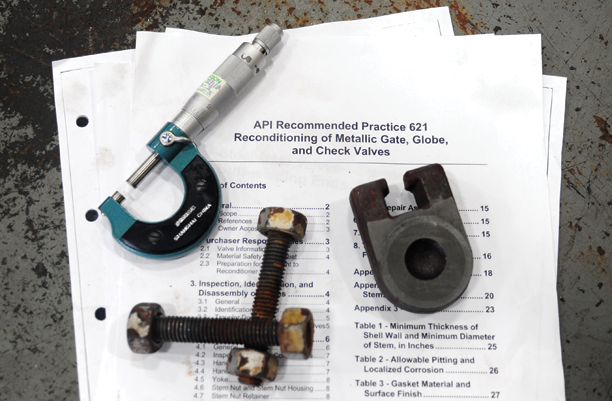

But labor rates for trained valve technicians have risen significantly over the last two decades as the workforce aged. This, plus the requirement to repair valves to tighter specifications such as American Petroleum Institute (API) RP621 valve repair standard, have raised the total cost of valve repair.

What this means is that the line between an economically repairable valve or a decision to replace with a new valve has seen a distinctive rise in size and pressure classes. Today, many refiners will not even consider repairing Class 150 cast-steel valves less than nominal pipe size (NPS) 12. Other refiners bump up the repair threshold to NPS 20. In Class 300, the economical-to-repair size limit drops to around NPS 10 for cast-steel-bodied valves. It drops even lower for valves in Class 600 and above.

So far, we’re talking about commodity gate, globe and check valves, which make up the bulk of refinery and process plant valve populations. But what about more expensive and more exotic valves? When the body material becomes chrome/moly or stainless steel, the repair/no-repair threshold drops significantly. Here, an NPS 6-inch Class 150 in CF8M (cast 316ss) material becomes cost effective to repair. However, as the austenitic stainless steels (300 series) become more commoditized, that go/no-go repair threshold continues climbing up just as the plain carbon steel plot line did years ago.

CRITICAL VALVES

Most owner/end users have some valves in their facilities that are more critical than others. These valves may see much higher pressures, be larger in size, be motor-operated or convey hazardous or lethal media. The TCO formula for these critical valves is a bit different. They must be maintained at a higher level than the commodity valves so proper repair is even more important. Oftentimes, additional nondestructive evaluation is called for, and special testing is required. These valves almost always take more expertise, technology and time to repair. This translates into higher repair cost.

Sometimes a new critical valve is available and the owner/end user has to decide whether or not to issue a purchase order for the repair or order new equipment. A rule of thumb for this decision is that if the cost of repair exceeds about 60−65% of the cost of the new valve, then a new valve is ordered.

Replacement with new equipment is not always an option, however, because these valves are often special-order, highly engineered valves with long lead times. In those cases, the decision becomes easy: The valve is repaired. In some cases, repair of specialized valves can cost more than a replacement valve would cost. Another factor in deciding whether or not to repair is the robustness of the original valve compared to the perceived robustness of a new replacement valve.

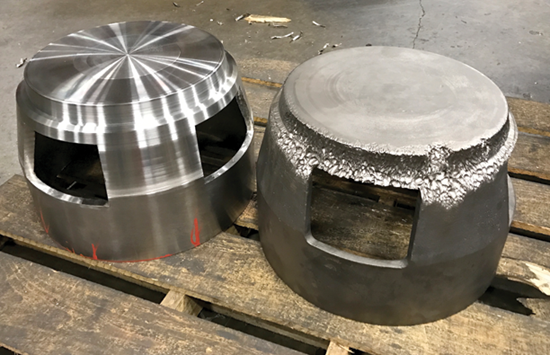

TEARDOWN AND INSPECTION

Unless a defect or problem is a painfully obvious one such as a casting leak through the side of the valve body, an investigation must be made first. This repair investigation is called tear down and inspection (TDI). TDI is where the problems are discovered, and the diagnosis is made. Most valve repair operations of critical valves begin with TDI, while in some cases, the owner may not ask for an initial TDI. TDI is almost always a separate billable item to cover the repair company’s costs for the inspection in case the valve is scrapped and no additional repair work is performed. Usually, the initial purchase order to a valve service company is just for the initial TDI.

TDI involves complete disassembly of the valve and examination of all the component parts. In some cases, a pretest is performed before the disassembly process. Once the valve is disassembled, any corroded or discolored parts are blasted or chemically cleaned to get the parts down to bare metal so that a careful inspection can be made. The visual inspection is augmented by measurement of key components. Sometimes additional nondestructive evaluations such as dye penetrant (PT), magnetic particle (MT), positive material inspection (PMI) or radiography (RT) are performed.

With all the parts’ inspections completed, the repair facility can prepare a scope of work and give an expected repair price, which includes the purchase of new parts, if they are available. The valve owner will then make the decision to repair or replace.

Although we’ve been talking about linear valves and check valves so far in this article, the process for quarter-turn valves has some similarities but also some differences.

QUARTER-TURN VALVES

For soft-seated ball valves, it’s vital to procure exact OEM replacement soft goods if they are available. By going back with the original OEM seals, tolerances can be maintained, and proper operation is better assured. This also ensures that during the valve’s next turnaround, OEM replacement parts will still fit. The cost of OEM parts is usually higher, but they should be the choice when available from the OEM. Parts are usually billed on a cost-plus-20% or so basis.

Metal-seated ball valves are slightly more difficult and potentially costly to repair because of the non-resilient nature of their seats and less-forgiving finishes and tolerances. For this reason, some of the severe-service ball valve manufacturers provide their own repair services. While OEM repair can be an excellent choice because of the direct access to OEM engineering and parts, possible drawbacks also exist, depending upon the situation and repair capabilities of the OEM.

These include: 1) The owner/end user usually prefers to minimize the number of purchase orders issued for valve repair on a turnaround, and sending every valve back to the OEM for repair involves cumbersome paperwork, and 2) OEM repair operations sometimes compete with production work, especially when machining or welding is involved, so valve repair work is sometimes pushed aside for project work.

High-performance butterfly valves see a greater percentage of OEM repair. The angles and tolerances of these valves are critical and usually, the OEM has the benefit of special jigs and fixtures that can make repair of the valves quicker and more economical.

Other valve types that favor OEM repair (or at least very strong OEM/repair facility relationships) are control valves. In general, they do not even fall under the same plant umbrella as block valves do. The control valves, with their critical regulating function to perform, are usually handled by the instrumentation group in the plant. The coordination of their repair falls under their responsibility as well. Since the control valves are more than final control elements, the repair facility needs to have an excellent understanding of the actuator, positioner and control system with which the valve interfaces, which is why OEM repair facilities see a much greater percentage of these valves during outages.

PRESSURE RELIEF VALVES

Repairing pressure relief valves (PRVs) is a special case. Since these valves perform a critical safety-related function in the plant, repairing them is heavily scrutinized by governmental agencies, the valve manufacturer and the owner/end user. There are strict rules established by the American Society of Mechanical Engineers (ASME) National Board (NB), that describe in detail repair procedures to be followed. Included in these requirements is the insistence on OEM replacement parts if the valve is to be restamped.

Since PRVs are repaired on regular schedules and they generally are not operated frequently, their repair costs can usually be estimated fairly accurately ahead of time. The repair process normally involves a pretest, followed by the typical TDI, and measurement and inspection of key components. The machining of parts and especially welding of any component is tightly controlled by the repair section of the NB code. Following repair and/or parts replacement, the PRV must pass a tight test procedure that ensures the valve will function as required.

IN-LINE REPAIR

Process plants and refineries also have large and unusual special-purpose valves that have to be repaired periodically. Giant, high-temperature flue gas and catalyst slide valves, which can weigh 20 tons or more, are examples of these types of valves. The repair of valves this large must be accomplished by field service (in-line) repair. Any in-line valve repair is going to be more expensive because of the logistics involved.

Other valves that are almost always repaired in place include virtually all welded-in valves. In-line valve repair is usually performed on critical buttweld-end power plant valves. Any machining, lapping or welding equipment must be portable to be brought to the jobsite and transported to the valve in need of repair. Just the handling of the equipment can require the creation of special temporary scaffolding as well as the availability of cranes and lifts. Normally, all equipment brought to the jobsite for field service repair is billed to the customer on a per-day basis.

Labor rates for field service work can be anywhere from 50−100% higher than shop rates. This is because of the job conditions and the stringent requirements of working in a plant.

The most dangerous and expensive field service valve repair occurs in nuclear power plants. Personnel performing this work are the cream of the valve repair crop because any mistake made during repair can be deadly. Needless to say, the rates for field service repair in nuclear facilities are very high.

SHOP WORKFLOW

One of the biggest issues valve repair companies face is the balance of manpower. A company may participate in six to eight major repair turnarounds a year, plus a number of smaller repair jobs. A large valve repair turnaround can require two or three shifts of straight, 24-hours-a-day work until all the valves are repaired. These types of jobs require many highly qualified technicians to man the multiple shifts. An issue comes up when there are no turnarounds in house and the number of random repair jobs is low, a situation that leaves many highly paid personnel sweeping the floor or doing other non-billable work.

Because of the up-and-down monthly business cycles in valve repair, assessing the financial viability of a repair company has to take into account a 12-month business cycle, as some months can be very profitable, while others can be stained with red ink.

SPECIAL PROCESSES

Some repair jobs require techniques or processes that are above and beyond the normal daily routine. These include the qualification of very specific welding procedures. A good repair facility working on linear and quarter-turn valves will probably have 100 to 150 welding procedures qualified in accordance with the requirements of the ASME Boiler and Pressure Vessel Code. However, it is not unusual for an end user to request special welding procedures that exceed the requirements of Section IX of the boiler code. These procedures are usually processed on a hot-rush basis, with the cost for these special procedures added to the invoice.

A logistical and economic advantage for repair facilities is having vertical integration. Not having to send components out for special processes such as welding, nondestructive evaluation and heat treatment can save the customer both time and money.

STANDARDIZED REPAIR

It is rare for a customer in the oil and gas industry to ask a valve service firm to just repair a valve. Specific criteria and procedures are created that need to be followed. While some companies have their own repair standards, many reference the appropriate and available API repair documents.

API’s RP621 refinery valve repair document is thorough. It requires numerous examinations and inspections of valve components. In addition to the inspection phase, all repair activities must be documented in detail on forms submitted to the owner/end user following the repair process. This equates to much paperwork or a thorough enterprise resource planning (ERP) system to digitally document all repair activities, including inspection and test reports. All of these inspections and documentation take time. This is why the thorough repairs in accordance with RP621 cost a lot more than a cursory “clean up and retest” repair.

While the API RP621 document is specified for gate, globe and check valves, currently no repair standard exists for quarter-turn refinery valves. The API refinery valve group has considered creating such a document and could begin work on it in the next few years.

On the midstream side of the oil and gas industry, API has a repair document for valves built in accordance with the API 6D Pipeline Valves design standard. This document is API 6DR, Repair of Pipeline Valves. Repairing valves to this standard is also going to cost more because of the repair details and documentation requirements.

WATERWORKS VALVES

Most valve repair is focused primarily on the refining, petrochemical, chemical and power industries because of the harsh operating conditions that valves in these services see. However, valves in water service require repair from time to time, although not as often as process industry or power valves. Waterworks valves that see the most repair activity include large outer diameter gate, ball and butterfly valves as well as valves in dams and hydro-electric facilities. Since most of these valves are difficult to remove, they are repaired in place and dictate the higher in-line repair pricing.

CONCLUSION

It would be great if all repairs could be quoted at a set price before the valves are inspected, but many factors go into the costs and pricing of fixing a valve. While set pricing is occasionally done, these ahead-of-time, no-inspection-basis price quotes are necessarily high to cover all possible contingencies.

Performing valve repair that is both profitable for the service facility and economical for the owner/end user is the goal for every repair job. At the end of the day or the end of the turnaround, the objective is to have customers that are confident they received value for their repair dollars and a repair company that was able to make a reasonable profit on its labors.

GREG JOHNSON is president of United Valve (www.unitedvalve.com). He is a contributing editor to VALVE Magazine and a current Valve Repair Council board member. He also serves as chairman of the VMA Communications Committee, is a founding member of the VMA Education & Training Committee and is past president of the Manufacturers Standardization Society. Reach him at greg1950@unitedvalve.com.

RELATED CONTENT

-

Effective Check Valve Selection and Placement for Industrial Piping Systems

When planning a check valve installation, the primary goal is to achieve a valve and piping system that offers the longest service life at the lowest cost.

-

Do Current Headwinds Affect the Repair or Replace Decision for Valves?

Perspectives from a valve repair company and and OEM on what drives end users to make this determination.

-

Creating a Standard for Severe Service Valves

Severe service valves are offered in several standard designs, including non-return, isolation and control types.

Unloading large gate valve.jpg;maxWidth=214)