The U.S. Valve Industry in World War II

While valves didn’t directly sink ships or shoot down planes, the American valve industry played an important role in winning World War II for the allies.

#valvehistory

The expertise and productivity that the industry developed over the first third of the 20th century was rapidly eclipsed during the years 1940 to 1945. Out of necessity, new designs and materials were called upon to control new processes in the chemical, petrochemical and refining industries.

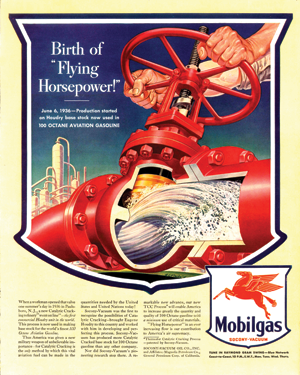

For example, “I think we wouldn’t have won the Battle of Britain without 100 octane fuel—but we did have the 100 octane,” Geoffrey Lloyd, Great Britain’s petroleum director, said. Germany’s lack of sufficient amounts of 100-octane aircraft fuel meant that the British Spitfires and Hurricanes could climb faster, fly higher and fly faster that the swastika-emblazoned enemy aircraft they faced.

The valve industry helped the petroleum industry by providing flow control for the upgraded cracking processes that allowed the higher 100-octane output. In addition, the valve industry also helped provide the piping systems that created two more war-

winning chemicals—Toluene for explosives and Butadiene for synthetic rubber.

Toluene is the most important ingredient in the making of TNT, the American explosive of choice during the war. Increased capacity and processes at American Toluene plants ensured the war production conveyor belt of bombs and shells would be an endless one.

Before hostilities began, American steel wheels were gripped by tires made of imported natural rubber, most of it from the East Indies. As war clouds gathered into a raging storm in the Pacific, the United States needed an alternative to natural rubber, and it needed huge quantities in a short amount of time. American chemists perfected the development of synthetic rubber on a massive scale by increasing the output of Butadiene, a petroleum byproduct, which is the key ingredient in synthetic rubber. Now, thousands of planes and vehicles would have abundant supplies of high-quality tires and other rubber goods.

The budding pre-war petrochemical industry grew up virtually overnight, producing vital chemicals that helped to ensure victory. Every one of the new plants needed an abundance of valves in all types and sizes. During the war years, the valve industry was handed fluid process variables they had not seen before in the form of higher temperatures, unusual corrosion effects and ultra-high (for the time) pressures. These new challenges resulted in the creation of new alloys and new valve designs that still serve industry today.

AIDING FUEL TRANSPORT

Another area where the valve industry earned its stripes was in the control of new, larger critical petroleum pipelines. During the first months of the war, the petroleum tanker route from the Gulf Coast to the northeastern United States was interrupted by deadly attacks by German U-boats. This resulted in dangerous shortages of petroleum in the manufacturing centers of the Northeast. New emergency pipelines such as the “Big Inch,” a 20-inch crude and gasoline line, which ran from the Gulf Coast to the Northeast, solved the transportation problem.

The Big Inch could move product at the rate of 235,000 barrels (about 9.9 million gallons) a day. The pipeline was dotted with isolation valves throughout its 1,475-mile length from Beaumont, TX to Linden, NJ. In addition, multi-valve pumping stations were needed throughout the length of the line. Additional trunk pipelines as well as smaller feeder lines required vast quantities of pipeline valves, mostly built to American Petroleum Institute API-6D standards.

ON THE WATER

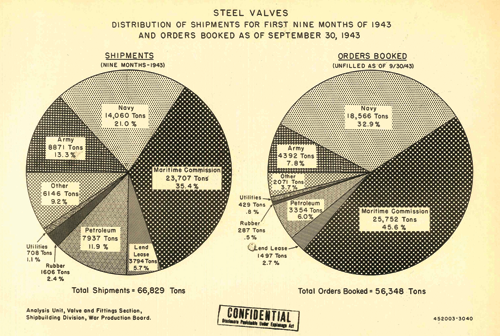

Although the oil and gas industries used a huge quantity of valves, the biggest users of America’s valve output were the Navy and Merchant Marines. The nation’s shipyards launched over 4,000 ships during the war. With each ship averaging about 2,000 valves, that meant the valve industry produced at least 10 million marine valves during the four-year period.

America’s valve manufacturers went above and beyond the call of duty to do more than their share, producing millions of valves and fittings during the four years of wartime. A letter from WPB written in late 1943 to the valve industry complemented the manufacturers on their “enviable record of production.” What’s more, the new materials, processes and production techniques perfected during those war years ensured U.S. valve market domination for at least another 30 to 40 years.

GREG JOHNSON is president of United Valve (www.unitedvalve.com), Houston, and is a contributing editor to Valve Magazine. He serves as chairman of VMA’s Education & Training Committee, is a member of the VMA Communications Committee and is on the board of the Manufacturers Standardization Society. Reach him at greg1950@unitedvalve.com.

As the Valve Manufacturers Association gears up to celebrate its 75th anniversary in 2013, we present this series of articles on the history of valves, with the final installment scheduled to appear in mid-2013. At this year’s VMA 74th annual meeting (Sept. 20-22, 2012 in Half Moon Bay, CA), VMA will unveil plans for the year leading up to the grand celebration, which will culminate at the association’s 75th annual meeting, Oct. 3-5, 2013 at The Breakers in Palm Beach, FL.

RELATED CONTENT

-

An Introduction to Axial Flow Check Valves

Check valves are self-actualizing devices that respond to both pressure and flow changes in a piping system.

-

Solenoid Valves: Direct Acting vs. Pilot-Operated

While presenting in a recent VMA Valve Basics 101 Course in Houston, I found myself in a familiar role: explaining solenoid valves (SOVs) to attendees. (I work with solenoids so much that one VMA member at that conference joked that I needed to be wearing an I Heart Solenoids t-shirt). During the hands-on “petting zoo” portion of the program, which involves smaller groups of attendees, one of the most frequently asked questions I get from people came up: What’s the difference between direct-acting and pilot-operated SOVs, and how do we make a choice?

-

Water Hammer

Water hammer is a shock wave transmitted through fluid contained in a piping system.

Unloading large gate valve.jpg;maxWidth=214)