Today’s Coatings Provide Solid Protection for Valves

Like anything made of metal, valves are subject to corrosion and other natural forces that compromise their performance.

#materials

Many coatings in use today, including both organic (paints, for example) and inorganic (zinc, chromium, nickel, aluminum and others) are applied to the outside surfaces to protect those surfaces. However, protecting the inside of a valve is a bit trickier because of the myriad of factors that come into play. This article concentrates on those challenges, covering coatings for the insides of valves that resist corrosion, prevent wear of the trim and other moving parts, and reduce erosion by abrasive media.

CHOICE OF METHODS AND MATERIALS

Many methods covered in this area are presented by the companies that make or provide them as alternatives to chrome plating—which is desirable because the newer coatings promise better properties and because chromium is facing ever-stricter environmental restrictions.

The requirements of individual applications determine which type of material is optimum for helping a valve resist corrosion, wear and erosion, says Dore Rosenblum, director of marketing, Sub-One Technology.

“For example, let’s say a valve is operating in a purely corrosive environment—gases flowing or something. Then, the goal is to make sure the coating is thick enough and doesn’t have any holes in it or pinholes that can cause corrosion,” Rosenblum explains.

The coating in this case could be a simpler one than a valve that had a very heavy sand flow, “where you have to worry quite a bit about erosion or abrasion or some other wear occurring in addition to corrosion,” he says.

For that second case, “we would create … a different type of coating that would be able to support the erosive flow through it and protect against damaging the surface of the valve,” he explains.

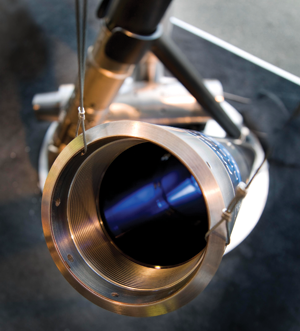

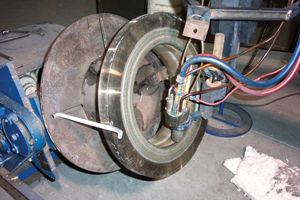

Hardcoating (Figure 2), which deposits a fairly thin layer of material and is often done with a thermal spraying technique, is distinguishable from hardfacing, which uses a form of welding for a thicker deposit, though considerable overlap in applications exists. The choice of which to use “usually has to do with the geometry of the part followed up by the volume of pieces that needs to be done,” says Ozzie Bell, manager, business development, Deloro Stellite. Manual methods used include MIG or TIG welding or oxyacetylene. If volumes are high and the part geometry is simple, he continues, “then there will be an automated process where we would have something like a plasma transferred arc piece of equipment being used, or an HVOF [high velocity oxygen fuel] system.” (Figure 1)

One of the oldest hardfacing materials used in valves is Stellite 6 (the name Stellite was trademarked in 1911), which is based on cobalt, chrome and tungsten carbide. However, Tribaloy alloys are increasing in popularity; the alloy consists of cobalt, chromium and molybdenum. Bell explains that: “They tend to stand up better under high abrasion and high corrosion applications.” They’re typically “used on the trim, on stem, seats, some bushings and possibly some of the flapper valves,” he says.

Another hardcoating gaining favor is Hardide Coatings’ tungsten carbide-based material, which consists of tungsten carbide nanoparticles dispersed in a tungsten metal matrix. This material is applied using chemical vapor deposition (CVD), which can coat both external and internal parts. The coating has been approved for use on a new line of coated metal ball and seats.

Meanwhile, Sub-One Technology uses a different deposition technique; the company employs a process applied by using “hollow cathode plasma immersion ion processing,” which can deposit carbon-based coatings, metal carbides and oxides—for example silicon, tantalum and chromium carbides—and diamond-like carbon films on the insides of objects (Figure 3). As this description implies, the process does not involve putting a part in a vacuum chamber and spraying or bombarding it with the material. Instead, says Rosenblum, “we … create a chamber within the part where we create a vacuum. We then apply the process so that it deposits the coating onto the internal surface.”

A LOOK AT THE FUTURE

Technology seldom stands still, and valve coatings are no exception. An interesting development at the Fraunhofer Institute for Manufacturing Engineering and Automation and the University of Duisburg-Essen was reported recently in an article in MIT’s Technology Review. The article explains that researchers are developing a way to electroplate metals containing liquid-filled nanoparticles. The hope is that these particles could be filled with liquid polymers or other materials that would be released if the plating was cracked or scratched, effectively sealing the crack and preventing corrosion.

This development and others like it ensure the valves of the future will have even more protection than those in years past.

Peter Cleaveland is a contributing editor to Valve Magazine. Reach him at pcleaveland@earthlink.net.

Composite Electroless Nickel Coatings

By Michael D. Feldstein

Electroless Nickel (EN) is generally an alloy of 88% to 99% nickel with the balance being phosphorous, boron or a few other possible elements depending on the specific requirements of an application. It can be applied to numerous metals, alloys and nonconductors with outstanding uniformity of coating thickness to complex geometries. In addition, its super fine particles can be added to form composite EN coatings that can enhance existing characteristics and add entirely new properties. Particles from a few nanometers up to about 50 microns in size can be incorporated into coatings that are a few microns up to many mils in thickness. The particles can comprise from 10% to over 40% of the coating depending on the particle size and application.

The widest use in the valve industry for these coatings is for increased wear resistance. Particles of many hard materials can be used in this process, such as diamond, silicon carbide, aluminum oxide, tungsten carbide, boron carbide and others. Diamond is the most common and has a Taber wear index of 1.159. Where low coefficient of friction, dry lubrication and repellency of water, oil and/or other liquids are crucial, the coating can contain 20% to 25% of sub-micron PTFE particles. Tests show that the lowest coefficient of friction is achievable when both mating parts are coated with composite EN-PTFE. Where high heat is a problem, composites with particles of ceramics such as boron nitride (which can withstand temperatures above 1562º F [850º C]) are used. When loading is high, the coefficient of friction of EN-BN and conventional EN actually decreases as the load increases.

EN coating can also be made to fluoresce under ultraviolet light, which can be useful in telling genuine OEM parts from counterfeit parts as well as in identifying specific manufacturing lots. The fluorescent material can even serve as an indicator layer, warning when the coating has worn off and replacement or recoating is necessary.

MICHAEL D. FELDSTEIN is president of Surface Technology, Inc. Reach him at Michael@surfacetechnology.com.

RELATED CONTENT

-

PFAS Chemicals and PTFE: Should the Valve Industry Be Concerned?

Legislation moving through Congress could affect the future use of thousands of PFAS chemicals (per- and polyfluoroalkyl). The house passed H.R. 2467 in July of 2021 and, though the bill is general in nature, it assigns the responsibility to the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) for determining which PFAS chemicals will be controlled or banned altogether.

-

Ni-Cr-Mo Alloys

Q: How do I know what the best type of Ni-Cr-Mo alloy will be for a particular application?

-

New Technologies Solve Severe Cavitation Problems

An advanced anti-cavitation control valve design enabled by 3D metal printing solved a power plant’s severe cavitation problem and dramatically improved its bottom line.

Unloading large gate valve.jpg;maxWidth=214)