Valves Help Achieve Net-Zero Water Use

With drought and climate change affecting countries around the world, there is a tremendous need for development of sustainable architecture.

#water-wastewater

The CSL employs several strategies to capture and treat all water on site for later use. This was a new construction that allowed Phipps to meet the living building challenge, which was achieved in 2013. The Living Building Challenge is an international sustainable building certification program created in 2006 by the non-profit International Living Future Institute, which promotes the most advanced measurement of sustainability in the built environment. This is more rigorous than green certification schemes such as LEED or BREEAM. All sanitary water that comes from sinks and fountains, and that is used to flush toilets, is treated on site and reused for flushing. The only water taken from the municipal system is that used for drinking and hand washing, as the health department requires particular treatments for those purposes.

According to Jason Wirick, director of facilities and sustainability management at Phipps, it takes many valves to make this system work, particularly check valves and three-way valves, which are utilized to divert water to the different areas within the system as needs arise.

Rainwater harvesting

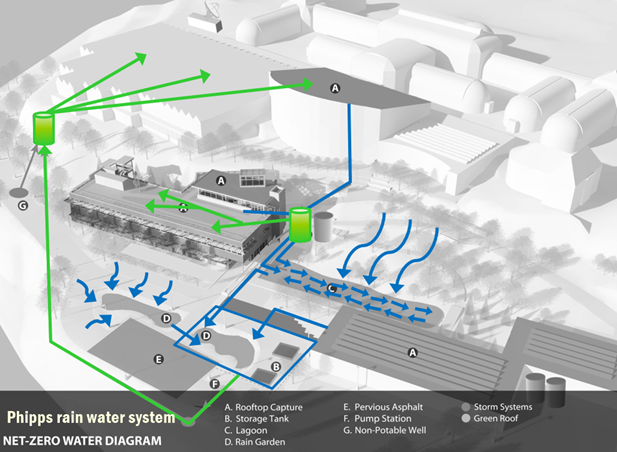

Rainwater is collected from the roof of the structure adjacent to the CSL—the Tropical Forest Conservatory (“A” in Figure 1); the water flows into a cistern and can be used for toilet flushing or irrigation needs. A three-way valve is used to send the water to toilets, to hoses for irrigation or, if there is too much for either of those systems, it is sent to the lagoon.

The storm water lagoon, (“C”) is a wetland filled with turtles and plants. It is a natural filtration system complete with water fountains that are part of the beautiful gardens of the property. The lagoon cleans itself while being an amenity for visitors.

If there is so much rain the lagoon overflows, the excess goes to another series of in-ground tanks. The rain garden (“D”) is comprised of ponds, underneath which is an unlined block tank from which the rain can percolate back into the ground over time. “If that is overwhelmed or we want to capture that water for another purpose, a valve is used to send that water into Tank “G” [and then] into another line cistern where the water can be pumped into other systems in the campus. We are just completing the integration of those systems now,” said Wirick.

While much of the freshwater system is operated initially by gravity, there are dozens of valves directing the flow in the wastewater system.

Blackwater Treatment on site

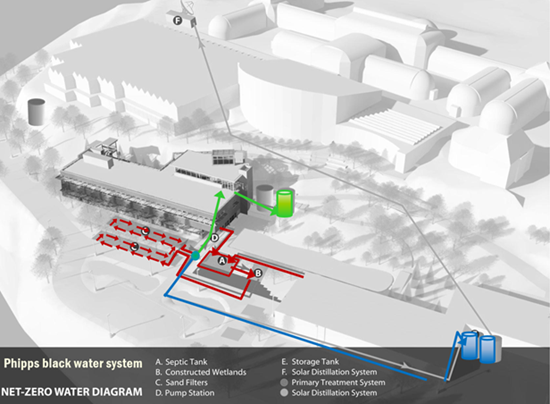

Raw sewage from toilet flushing is treated on the property. The process is depicted in Figure 2.

Once waste is flushed into the system, it goes into a settling tank (“A”) on the diagram. It is pumped into the constructed wetlands (“B”) at different times throughout the day, typically in 50-gallon increments. The plants in the wetlands use the waste as nutrients. After the water leaves that system, it is pumped into sand trenches (“C”) in doses. The sand, acting as a filter, scrubs the water, removing the cloudiness and turbidity. Then the water can come back into the building through micron filters. Next it is zapped by UV filters to destroy any remaining pathogens and then stored in a cistern (green cylinder in the diagram) where it waits for someone to flush the toilet. Then, just before the treated water reaches the toilets it is sent through another UV filter. Once it is flushed, the process starts all over again.

“There is some redundancy,” said Wirick. “If there was additional capacity, for example, the water can go through a three-way valve, and instead of the water going back into the building, the valve can divert the water into another series of cisterns on the other side of the campus. That water can then be sent to the upper campus for irrigation.”

The Valves

The valves help make it possible for Phipps operators to send the water where it needs to go through a series of pressurized lines and pumps. “Much in the rainwater system works on gravity; the valves come into play when we start pressurizing lines,” said Wirick. “There are 3- or 4 three-way valves, and about 10 check valves in the sanitary treatment-reuse system.” Except for a few check valves and backflow preventers that are manually operated, these are smart valves and are operated mostly remotely from the CSL’s control center.

“It is all based on a computer system that has logic and code,” he said. “The code will say, ‘when water in this cistern is at a particular height, we have to push water to this area.’ That is all done through the automation system. This is what makes the valves smart. They are modulated with low-voltage signals sent from our automation system to the valves. Many of them are three-way valves with actuators that can push water in different directions.”

While no single segment of the CSL system is particularly unique or innovative, there is ingenuity in the way they are designed to operate, proving that beautiful spaces with lush gardens do not have to waste the most precious of commodities.

Kate Kunkel is senior editor of VALVE Magazine.

RELATED CONTENT

-

Check Valve Installation Considerations to Maximize Process Performance

Key considerations in successful check valve performance.

-

New Requirements for Actuator Sizing

After decades of confusion, the American Water Works Association has created new standards for actuator sizing that clear up some of the confusion and also provide guidance on where safety factors need to be applied.

-

The Biggest Valves: Sizes Growing in Step with Greater Demand

Valve manufacturers that have the expertise, skills, equipment and facilities to produce large valves are rare.

Unloading large gate valve.jpg;maxWidth=214)