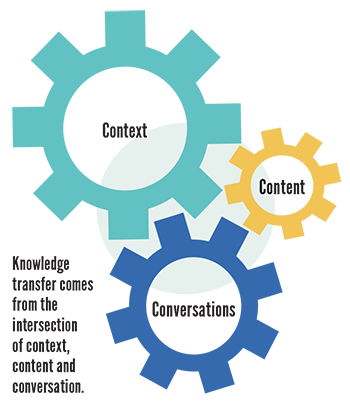

To do our jobs, we all need the necessary knowledge. Typically, newer employees learn from more experienced folks, and while that happens naturally to some extent, the transfer of knowledge can be encouraged and facilitated.

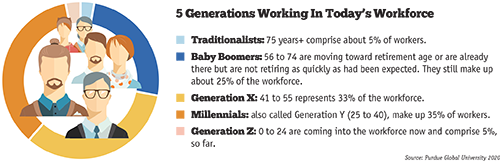

Considering the large age range among today’s older and younger staff, the good news is the gap between generations is closing when it comes to knowledge transfer.

The bad news? It’s been 15 years since the start of what we call “the big crew change”—with members of the Baby Boom generation retiring—and many companies think that “hope” is a method of dealing with this change.

KNOWLEDGE TRANSFER IN REAL LIFE

When working for BP in 1988, I found myself in a helicopter in Colombia headed for an oil drilling site as part of an initiative for business unit leaders to learn from each other and improve our company performance. Landing on a drill site to tour the operation, I learned the Colombian team had installed the same air compressors used in development of the Endicott Field I had worked on in Alaska. Their young maintenance manager explained the equipment was running at only 50% uptime. This meant half the time they could not drill, resulting in poor overall efficiency. So I popped open my satellite phone and called the senior maintenance manager in Alaska. I explained the situation and, with the help of a translator, connected him with the Colombian maintenance manager and then left for the evening.

When I returned the next day, everyone was happy—especially the maintenance manager. The manager in Alaska passed along some of his hard-earned knowledge about running the compressor that was not in the equipment manual. The uptime had improved to 80% overnight.

MY GENERATION AND YOURS

Today’s workplace is made up of five different generations, all of whom contribute and require knowledge. Because of their life experiences, different people and different generations have their own preferred ways of acquiring and sharing knowledge.

Some workers do well with structured classroom-type learning. Many of those who grew up with computers and the internet like and expect to acquire knowledge on the fly from online sources.

Your company can start today using methods to promote the transfer of knowledge and accelerate team and organizational performance.

Traditional methods such as mentoring, apprenticeships and sharing stories about solving problems are ideal for helping younger workers and those who are changing focus acquire expertise one-on-one from experienced personnel. Other approaches include social media, digital knowledge transfer (podcasts, videos, various virtual methods), communities of practice (groups of people who share common interests and concerns) and fast-learning techniques (described below).

GETTING KNOWLEDGE FROM HERE TO THERE

Since my early experience at that drilling rig in Colombia, I’ve learned a lot about knowledge and how it is passed along. Here are some basics:

- Knowledge is not limited to certain people. It can come from anyone.

- Knowledge doesn’t transfer by itself. It takes energy and time to go from one person or group to another, especially if it is complex.

- Knowledge transfer is everyone’s job. We all suffer from information overload, but have you ever heard someone say they have enough knowledge?

We need knowledge to live long and prosper. We need knowledge to maximize business performance while caring for the environment.

A lot of this information about intergenerational knowledge transfer comes from research initiated in 2007 by The Conference Board. The member-driven think tank studied 10 companies to ascertain which knowledge transfer techniques work and when to use them, as well as how to enhance cross-generation knowledge transfer. The project has been continuously renewed from 2010 through this year.

FAST-LEARNING TECHNIQUES

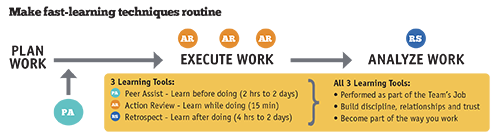

A number of powerful techniques exist for making multigenerational knowledge transfer routine in an organization. They’re fast, they work, and they make a difference. They involve learning before doing (peer assist), learning while doing (action review) and learning after doing (retrospect).

Peer Assist

This learning-before-doing facilitated work session can last anywhere from an hour or two to a couple of days depending on the complexity of the knowledge you want to transfer. Visiting peers share their knowledge with the home-team peers because they want to help. This is not about the visitors telling the home team what’s wrong; it’s about sharing and learning from each other about what to do differently. The process is done early enough to make a difference in future behavior. Often the people who come to “give” and share, whether it’s face-to-face or virtual, get a lot out of it too.

The home team begins the peer assist session. “Here’s what we know, here’s our challenge, and here’s what we don’t know and need help with.” That opens up the floodgates for people to share.

Then the visiting peers share what they know in their context, stories and experiences. They are not critiquing the home team. Rather, they say, “Here’s what I learned when I did something similar.” At this point, you are moving toward all the people in the room knowing more together than they did as individuals when they entered the room. That sets the stage for the home team to consider what they should do differently, what they should start, stop or change. At that point, the group often makes a commitment to do something different going forward.

Here is an example of peers assisting each other virtually:

Several years ago, an oil drilling team in Norway was a couple of months away from drilling their first deep-water, high-pressure well in 30 years. Remembering what happened with Deep Water Horizon in the Gulf of Mexico, the government was concerned and needed to be convinced of the project’s safety.

We asked the drilling team to reach out to their personal networks to see who had experience with cement casing in high-pressure environments and could share their knowledge and make a difference.

In a few days, the drilling team found eight expert peers from different countries who were willing to participate. They did not know each other, and 50% of them were millennials. In two hours they exchanged ideas and changed the Norway plan so it reduced cementing costs by a couple million dollars and demonstrated to the Norwegian government that they could drill safely.

Action Review

One of my favorite approaches, because it works in the moment and makes an immediate difference, is the action review. It’s a take-off from the Army’s after-action review (AAR) technique developed near the end of the Vietnam War. It is a simple and fast tool for individuals and multigenerational teams in the field, on the job or in a work crew.

An action review involves answering four simple questions. It can take just 15 minutes to transfer knowledge, improve work and build team relationships and trust. The action review can be used when you need it, in the moment of any identifiable event, sub-task, milestone or something the team has experienced. The four questions are as follows:

- What was supposed to happen? That’s usually the first big win because everyone may not have talked in advance about what they expected to happen on this particular job, task or event.

- What actually happened? You get to the truth from direct observation.

- Why is there a difference? You talk about why there was a difference between what was supposed to happen and what actually happened.

- What can we learn from this and do right now? The team comes up with the next actions.

This powerful technique is fast, easy to remember and works with whoever is on the team.

Retrospect

A facilitated, forward-looking, team work session, the retrospect ranges from a half-day to a couple days for a major project and takes place soon after a milestone or the end of a project. Think of this as a lessons-learned technique. It goes into more detail than the action review, mainly because it is applied to a larger scope of work, and it is also geared toward surfacing and creating new knowledge that can often be used in different contexts.

Built on a process of inquiry, this is not just a “hot wash” or debrief. It examines in depth what happened and gets to the why. It makes learning conscious and explicit, so the learning becomes embedded in the people in the session who just did the work. They now have knowledge they can reuse the next time they do a similar project. In addition, this retrospect process can capture and package this new knowledge for reuse by others.

START WITH A PLAN

Every project starts with planning. If you don’t know everything needed to accomplish the work, do a peer assist to get better informed and have the answers it takes to move forward. While executing the work, do pause-and-learn action reviews to learn quickly as you go. When the project is complete, analyze and learn from it. This is what makes knowledge transfer sustainable. Companies employing these techniques don’t have a knowledge-loss problem.

The best results occur when these fast-learning techniques work together and are embedded in the organization so they become routine.

CAPTURING KNOWLEDGE OF RETIRING STAFF

When a seasoned, experienced person retires, the company stands to lose a lot of knowledge.

One approach to retaining the knowledge is to have your less experienced staff harvest the knowledge they need in their particular role, task or project. You would be amazed at how quickly the necessary understanding is transferred and how quickly someone can come up to speed in a particular profession or task.

The ultimate way of accomplishing this transfer, though, is redesigning jobs for knowledge transfer in phased retirement. When you know someone is planning to retire, set them up a year or so in advance to shed their normal activities and pick up knowledge transfer activities. Have them participate in peer assists, as mentors, as teachers of master classes or informal learning sessions.

Knowledge transfer can happen in many ways. The critical thing is to get started.

This article is based on a presentation given by Greenes at VMA’s Virtual Valve Forum, held in November 2020.

KENT GREENES is founder and president of Greenes Consulting. He also serves as Senior Fellow Human Capital & Program Director for The Conference Board’s Knowledge & Collaboration Council and Change & Transformation Council. Reach him at kent.greenes@conference-board.org.

RELATED CONTENT

-

Intermediate Class Valves, the Forgotten Classification

These days, piping designers use automated systems that default to standard classifications such as pressure classes of 150 to 2500 for valves and associated equipment.

-

DBB and DIB: Which is which?

The term “double block-and-bleed (DBB)” carries a lot of misconception when it’s used to describe valve functionality.

-

Process Instrumentation in Oil and Gas

Process instrumentation is an integral part of any process industry because it allows real time measurement and control of process variables such as levels, flow, pressure, temperature, pH and humidity.

Unloading large gate valve.jpg;maxWidth=214)