The Road to Valve Knowledge

Valve expertise is a journey, not a destination.

#basics

The key is to develop and feed a passion for information, and the best way to accomplish that is one step at a time and one subject at a time. Hopefully, the roadmap presented in this article can help some VALVE Magazine readers make the trip successfully.

THE TRAVELERS

Valve professionals come in many shapes, sizes and educational backgrounds. An interesting aspect of the industry is that everyone has the opportunity to become skilled in at least one facet of the business. It doesn’t matter whether a person has a degree in engineering or a degree in education, a two-year degree in music appreciation or just a general education degree: Everyone has access to the road to valve expertise.

The actual path each person takes will be different, but that’s a good thing, because in the end, each person’s expertise will be unique. A person with a degree in mechanical engineering, for example, has a path quite different than that of a person working his or her way up through the ranks department by department. The route may not always be clearly marked, but it’s there for everyone who has the desire and who makes that first step.

Let’s start with a typical employee in the industry: We’ll give that person a high school education and a few semesters of college. He or she is now in the sixth month of working for a manufacturer’s representative selling quarter-turn valves.

Goal number one should be to develop into the very best quarter-turn product salesperson. Or, if that scope of knowledge seems too big to tackle at first, the person should focus on an easily digestible part of the quarter-turn product range such as ball valves or butterfly valves. This requires commitment and desire, maybe forgoing a night or two a week of television binge-watching to increase valve skills. The goal should be to become the go-to person in the company or group for a product or valve type.

Being mentored is a great way to glean information, but that requires finding a willing mentor. Professionals who want to get ahead and who manage to locate someone in their organizations that can serve as a mentor should attach themselves to that person and ask all the questions they can dream up, just short of being a pest. But there is more to the journey than being mentored.

Here’s my idea of a roadmap:

- Take a valve basics course (VMA will be offering an expanded Valve Basics 101 course in the Houston area Oct. 3-5. See page 11).

- Ask questions.

- Ask more questions.

- Obtain copies of catalogs for as many current products in a chosen area of study (quarter-turn valves for the example above) as possible. The internet is full of them, just for the downloading.

- Obtain or copy older catalogs as well. The older catalogs are often full of informational material and in some cases, provide easier to understand examples and data. The older catalogs will also help to develop a history of the product range.

- Ask to visit a valve repair shop or OEM service center and look at valves in their disassembled state. Ask questions, take notes and take photographs when that’s allowed.

- Start assimilating all this material into a digital file or (for those who are old school) a hard copy binder.

- Read as many valve books as can be obtained. A later section of this article reviews many of the popular valve books published in the last few decades.

- For basic knowledge in the physics and mechanics of valve operation, a college text on applied physics is useful. Those who are mathematically challenged should not worry: the arithmetic required for the problems is very, very basic.

- Take the ASM International online course “Metallurgy for the Non-Metallurgist.” The course is not difficult and does not require any engineering background. The knowledge gleaned might even make a professional the go-to person for metallurgy in the company.

- Subscribe to as many industry magazines as can be obtained. Number one should be VALVE Magazine, which is free to U.S. and Canadian subscribers. There also are numerous other good industry magazines, some of which carry high subscription fees and some with low- to no-cost subscriptions.

- Finally, as information accumulates—pay it forward. Share what is learned with those around you. They will either learn something from it or confirm that the lessons being learned are correct.

If the goal is to gain actuator expertise or control valve expertise (as opposed to our example of quarter-turn valves), the road will be parallel, but will have some different scenery along the way.

The engineer’s path is slightly different. A graduate engineer should already have a good knowledge of basic metallurgy and fluid statics and dynamics, for example, so the metallurgy and industrial physics course material would be redundant. However, the rest of the pathway still applies.

STANDARDS AND SPECIFICATIONS AS A LEARNING TOOL

The refining, petrochemical and chemical industries rely on a multitude of American Petroleum Institute (API) valve standards and recommended practices. The best way to gain access to API standards (aside from buying the current finished documents) is to locate an API committee member and ask that person to send copies of any current working drafts. Superseded documents can also provide a wealth of basic information and are often available cheap via eBay or other online sources. Those with contacts at end-user or engineering companies can ask them for outdated versions of valve specifications, since they are often discarded anyway.

Other sources of valuable information are end-user or engineering-contractor specifications. These company or project-specific specs often contain application information not found in other places. Don’t worry if some of the information appears to be above current valve knowledge level. The information provided in these standards and specifications will help fill in some knowledge gaps down the road.

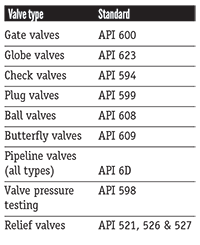

Here are some valve API standards and the valve types they pertain to:

If the oil and gas industry is not your bailiwick, there are informative standards for other industries. The waterworks industry has standards for a variety of valve types, as well as actuators. People in the water/wastewater field should be aware of the standards put out by the American Water Works Association. For those in the control valve industry, the International Society of Automation (ISA) has standards for final control elements.

ONLINE AND HIGHLY INFORMATIVE

There are excellent online sources of valve information available for downloading by anyone.

For example, the Department of Energy (DOE) has an excellent, 50-page valve handbook that can be pulled down from the agency’s website. It is the DOE Fundamentals Handbook, Mechanical Science, Volume 2 (DOE-HDBK-1018/2-93). The handbook was originally targeted to the nuclear industry, but the information is applicable to all valve industry segments, and best of all, it’s free.

The most thorough valve application guide available for free download is the Electric Power Research Institute’s (EPRI) Valve Application, Maintenance and Repair Guide. While much information on power plant applications is in that guide, including repair and maintenance, the whopping 400-plus pages also contains a huge amount of general knowledge.

Another free EPRI document is its Guide for the Application and Use of Valves in Power Plant Systems. While this guide obviously focuses on power applications, the overall valve information contained in its 500 pages is impressive.

To access EPRI documents on the web, go to EPRI.com. Then click on EPRI Portfolio and after the new page loads, insert either of the article titles in the search box. Other informative titles available from EPRI are also available there: Just enter “valves” in the portfolio search box, and they’ll pop up. However, many of the documents are not free and have price tags of $25,000 and higher—feel free to ignore those documents!

Valve seminars and forums also can be informative and are often topic-specific in focus. VMA puts on a valve technical program each year that offers many interesting and useful tracks that go beyond the basics. API also holds a Tank, Valves & Piping Conference in early winter each year, offering a dozen or so informative valve presentations.

As this article mentions, there are excellent resources available for free on the internet. However, here’s a “caveat emptor”: even though the buyer is paying nothing for the information, he or she needs to be aware and diligent in assessing the credibility of internet sources. There also are companies putting lots of words and images out there for downloading that almost plagiarize others works and some don’t have the capability of getting it right, much less the ability to create their own “expert” content. Usually, the larger the company and the more well-known it is, the more reliable the information.

A dozen or so valve books have been written over the past four or five decades. Even though a book may have been published before a valve professional is born, it doesn’t mean that the information is bogus or out-of-date. Many timeless texts are available on the used-book market that can really help with the journey to expertise. The following section contains short reviews of many of the valve books written since about 1965. Also included are a couple of non-valve titles that are nevertheless very informative. Any out-of-print books can be found on eBay and used book sites such as AbeBooks (www.abebooks.com).

Handbook of Valves and Actuators by Phillip Skousen: This book covers all the basics, including pressure ratings and valve types; however, it is first and foremost a reference for control valve professionals. Those in the control valve or control systems valve segment should reserve a space on their bookshelves for this publication.

Valve & Actuator Technology by Wayne Ulanski: Although primarily a quarter-turn valve volume, this book devotes nearly half of its 300 pages to quarter-turn actuation. Ulanski covers some areas not usually mentioned in valve books, such as fire-safe applications and testing. This is a good volume for anyone active in the quarter-turn segment of the industry.

Valve Selection & Specification Guide by Ron Merrick: Merrick’s book is an excellent candidate for the general valve professional’s library. The basics of all valve types, including materials and design, are covered. Because of the author’s easy-going writing style, the publication is an easy read. Other topics such as repair, modification and procurement are covered as well.

The Safety Relief Valve Handbook by Marc Hellemans: This is the go-to volume for those in the pressure-relief valve field. All the concepts of pressure integrity management devices are covered in this well-written, easy-to-read, full-color book.

BVAA Valve & Actuators User’s Manual published by the British Valve & Actuator Association (BVAA): This is a unique valve book because it combines advertisements of BVAA members with excellently written, full-color printed educational material. The book covers all valve types and the drawings and cut-away photographs are excellently reproduced. It draws heavily from the association’s excellent educational program and is a highly recommended volume for any valve library, especially those doing business in the United Kingdom (UK) or European Union.

The Valve Book published by Neles Jamesbury: This valve publication is a combination of brand marketing and specific quarter-turn valve information. The first half of the book focuses on general information, while the second half details specific Neles Jamesbury (now Metso Automation) products and applications. There is value, however, in the general information in the book as well as takeaways from the brand-specific anecdotes. It also contains information on quarter-turn, soft-seating design technology as well as some specific quarter-turn, control valve applications.

Valve Actuators by Chris Warnett: This actuator book is the culmination of the author’s 37 years in the valve actuator industry. The book is an excellent primer on actuators of all types. The well-written and -illustrated book is a must for those in the actuator or motor-operated valve industry.

Control Valve Primer published by Instrumentation Society of America (ISA): This should be on the shelf of anyone involved in control valves (final control elements) or control loop design and implementation. Drawing on the resources of ISA, the book covers control valve types, selection and sizing, materials and valve positioners in depth.

The Valve Primer: This little 4-inch by 6-inch book is the pocket reference for the valve industry. There are no frills, just easy-to-find information on virtually everything valve-

related. Everyone in the valve industry should own a copy of this primer. It is a great refresher for the experienced valve professional and a potential “I can answer that question in 60 seconds” book for the valve newbie.

Lyons Encyclopedia of Valves by Jerry Lyons: This encyclopedia contains something for both the experienced valve engineer and the industry newcomer. The illustrated, 72-page valve terminology section is thorough, though it focuses somewhat towards the control valve segment. Some very technical information in this book such as valve spring design and fluid power symbols and standards will only be appreciated by a specific group of valve professionals.

An Introductory Guide to Valve Selection by Smith & Vivian: This book, which is published in the United Kingdom, is general in scope. It also offers much of the same information found in the Lyons Encyclopedia. However, the publication does cover special valve applications along with a good overview of valves for upstream and midstream petroleum applications.

Crane Catalog #60—This catalog was printed nearly 60 years ago, but much of the information in its pages is timeless. By studying the gate, globe and check valve designs and materials, a valve professional can gain a good understanding of where many of our designs of today originated. Copies of the catalog are available on eBay where the book is often offered for sale at ridiculous prices aimed at ignorant plaintiff’s attorneys involved in the asbestos litigation industry. Don’t pay over $20-30 for a copy.

Fundamentals of Applied Physics by C. Thomas Olivo: This publication can be found used for less than $10. Covered in the content is basic machines, properties of liquids and solids, basic mechanics, threads, fluid power and electricity. An updated college textbook covering the same material is Applied Physics, which can be purchased used for about $20. The material is easy to comprehend and will help readers understand what happens to fluids under pressure and in motion. The basic mechanics segments also help in understanding stems and actuators and how they work.

Metallurgy for the Non-Metallurgist edited by Arthur C. Reardon: This book provides an important background for valve materials knowledge. Many material questions that come up along the valve expertise trail are answered in this book. Those professionals who can’t take the ASM course mentioned in my roadmap can use this volume as the next best thing.

Petroleum Refining in Nontechnical Language by William Leffler: This publication offers an excellent overview of refining operations. The material can be helpful for those supplying and specifying valves into the refining industry. Learning about customers’ businesses is always a positive thing. Those professionals involved in the downstream valve segment can rely on this volume for some great background information.

CONCLUSION

No one becomes an expert overnight, and the journey to valve expertise is no exception. The trip is much more of a steady jog than a sprinted race, so individuals need to take their time and enjoy the trip.

They also need to learn that the pace is occasionally disrupted by life’s realities. However, the best investment valve professionals can make is in themselves. Along the pathway to expertise, confidence will grow as the miles of lessons learned are collected, collated and shared. Soon the valve expertise learning trip will result in fewer and fewer questions asked and more and more questions answered.

The engine is running for valve professionals, so it’s time to hop in the car and get going.

GREG JOHNSON is president of United Valve (www.unitedvalve.com) in Houston. He is a contributing editor to VALVE Magazine, a past chairman of the Valve Repair Council and a current VRC board member. He also serves as chairman of VMA’s Education & Training Committee, is vice chairman of VMA’s Communications Committee and is past president of the Manufacturers Standardization Society.

RELATED CONTENT

-

Differences Between Double Block and Bleed and Double Isolation

There is an important distinction between DBB and DIB, as they often fall under the same category and are used interchangeably within the industry.

-

Introduction to Pressure Relief Devices - Part 1

When the pressure inside equipment such as boilers or pressure vessels increases beyond a specified value, the excess pressure may result in a catastrophic failure.

-

Understanding Torque for Quarter-Turn Valves

Valve manufacturers publish torques for their products so that actuation and mounting hardware can be properly selected.

Unloading large gate valve.jpg;maxWidth=214)